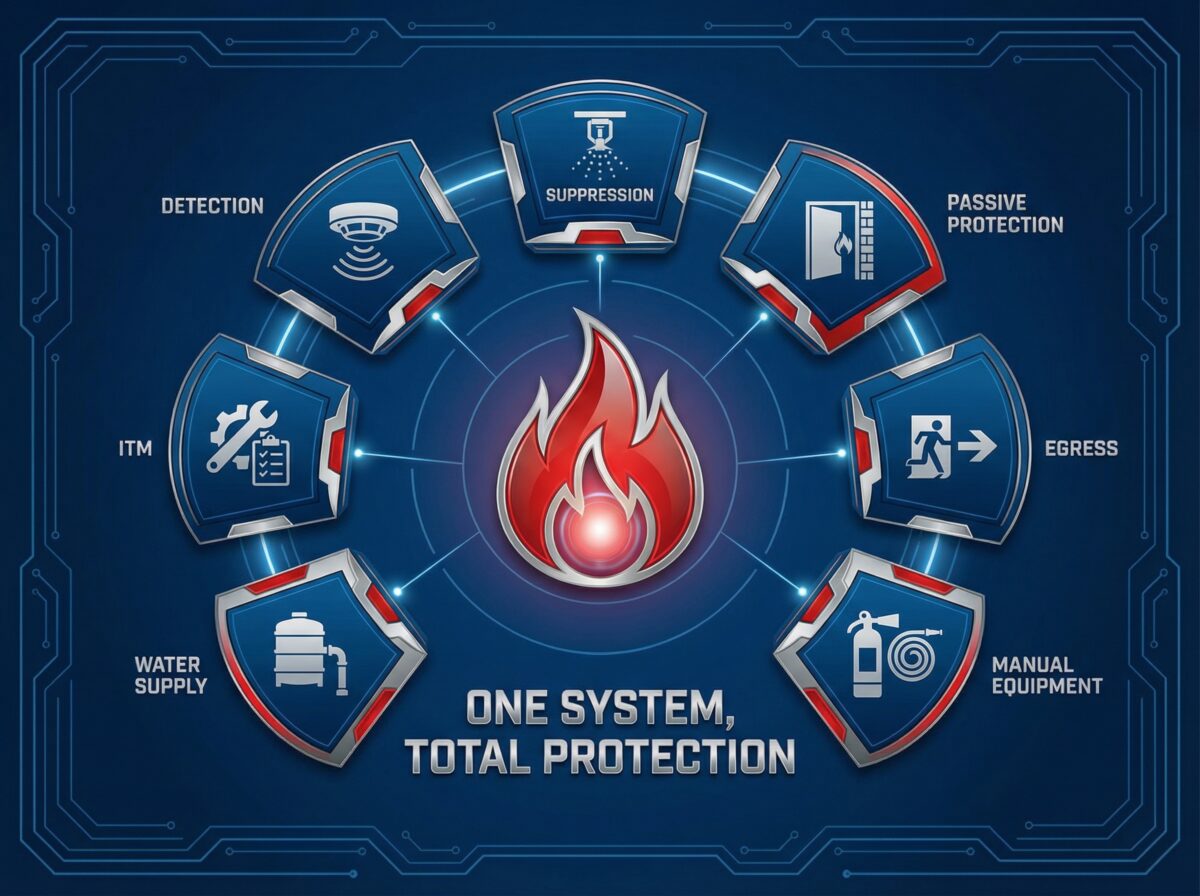

Total fire protection requires seven integrated components working as one system. Miss any element and protection fails when you need it most.

After implementing fire protection across 3,000+ facilities ranging from manufacturing plants to healthcare centers to high-rise office buildings, patterns emerge. Facilities with complete, integrated systems experience:

- 96% fire control rate when systems activate

- 78% less property damage compared to partial protection

- Zero multiple fatalities where systems operated properly

- Significantly reduced insurance premiums and code violation citations

Facilities with incomplete systems—even expensive ones—fail during actual fires. The difference isn’t equipment quality. It’s system completeness.

—

Component 1: Fire Detection Systems

Detection is the foundation. Everything else depends on knowing fire exists.

Detection Device Types by Application

Smoke detectors provide earliest warning in most commercial environments. Three technologies serve different needs:

Ionization detectors respond fastest to flaming fires with small smoke particles. Best for: Areas with minimal ambient dust, spaces where fast-flaming fires are expected, general office environments.

Photoelectric detectors excel at detecting smoldering fires producing larger smoke particles. Best for: Sleeping areas, locations with potential electrical fires, spaces where slow-burning materials are present.

Multi-sensor detectors combine optical and heat sensors with algorithms evaluating both inputs. Best for: Complex environments with varied fire risks, facilities requiring false alarm reduction, areas where single-technology detectors cause problems.

Heat detectors work where smoke detection creates false alarms—kitchens, manufacturing areas with dust or steam, vehicle maintenance facilities. They trigger on fixed temperature thresholds (typically 135°F-165°F) or rapid temperature rise rates.

Flame detectors use infrared or ultraviolet sensors detecting radiation from flames. Response time: 3-5 seconds. Best for: Outdoor areas, high-ceiling spaces, locations with flammable liquid or gas hazards.

Carbon monoxide detectors for fire protection (distinct from home safety CO detectors) respond faster to combustion products. They work in conjunction with smoke detection for comprehensive early warning.

Control Panel Architecture

The fire alarm control panel functions as the system brain, processing all detector signals and coordinating responses.

Conventional systems wire detectors in zones (typically 8-20 zones per panel). Alarm indicates which zone activated—narrowing fire location to specific building areas. Cost-effective for smaller facilities under 50,000 square feet.

Addressable systems assign unique addresses to each device. Control panel identifies exactly which detector triggered, enabling precise fire location. Essential for facilities over 50,000 square feet or complex layouts where zone-level location is insufficient.

Intelligent systems put computing power in each detector. Devices analyze smoke density, heat levels, and environmental factors before reporting fire conditions—reducing false alarms while maintaining sensitivity. Each detector communicates operational status, allowing predictive maintenance (cleaning needed, end of life approaching).

Wireless systems use secure radio communications eliminating wiring requirements. Ideal for historic buildings where cable installation damages architecture, facilities requiring rapid deployment, or areas where cable installation costs are prohibitive.

Integration Requirements

Detection systems must integrate with:

- Sprinkler system flow switches (confirming water delivery)

- Building access control (unlocking exit doors during emergencies)

- HVAC systems (smoke control sequencing)

- Elevator controls (recall to ground floor)

- Emergency notification systems (mass communication)

Facilities treating detection as standalone systems lose critical coordination during actual emergencies.

—

Component 2: Fire Suppression Systems

Detection without suppression is warning without protection.

Water-Based Suppression

Wet pipe sprinkler systems remain the most reliable protection method—pipes constantly filled with pressurized water, individual heads activate independently when heat breaks their mechanisms.

Effectiveness: Control fires in 96% of activations. Average industrial sprinkler head discharges 75-150 liters per minute—dramatically less than fire department hose streams (900 liters per minute), minimizing water damage while providing adequate fire control.

Design requirements per NFPA 13:

- Hydraulic calculations using only 90% of available water supply

- Head spacing and density matched to hazard classification

- Pipe sizing adequate for required flow rates

- Testing and maintenance per NFPA 25 schedules

Dry pipe systems fill pipes with pressurized air or nitrogen instead of water. When heads activate, air vents first, then water enters. Critical for: Unheated buildings, parking garages, freezing environments, outdoor protection.

Trade-off: 60-second maximum water delivery delay and higher corrosion potential from residual moisture and oxygen in pipes. Cost typically 40% higher than wet pipe equivalents.

Pre-action systems require two triggers before water enters pipes—fire detection event plus sprinkler head activation (single interlock) or detection event plus sprinkler operation plus manual activation (double interlock).

Best applications: Museums protecting irreplaceable artifacts, data centers with sensitive electronics, cold storage facilities, locations where accidental water release causes severe damage.

Deluge systems use open sprinkler heads across entire protected area. Fire detection system triggers simultaneous water application. Used for: Aircraft hangars, chemical storage, areas with potential for rapid fire spread across large spaces.

Gas-Based Suppression

Clean agent systems suppress fire without water damage—critical for protecting sensitive equipment, electronics, and irreplaceable materials.

Inergen systems use naturally occurring gas mixture (nitrogen, argon, CO₂) reducing oxygen levels to 12.5%—low enough to extinguish fire but safe for occupied spaces. Zero global warming potential. NFPA 2001 compliant.

FM-200 systems discharge colorless gas absorbing heat and interrupting combustion. Safe for occupied spaces but subject to EPA phase-down due to greenhouse gas classification. Discharge time: 10 seconds. Suppression achieved in under 30 seconds.

CO₂ systems displace oxygen to suffocate fires. Effective for Class A, B, and C fires with zero residue. However: CO₂ is toxic to humans—only use in unoccupied areas like electrical rooms, generator enclosures, or spaces with pre-discharge warning allowing evacuation.

Specialized Suppression

Foam-water systems apply mixture of water and foam concentrate creating blanket separating fuel from oxygen. Primary use: Flammable liquid fires (aircraft hangars, chemical processing, fuel storage).

Water mist systems disperse fine water droplets cooling fire and displacing oxygen while using 50-90% less water than conventional sprinklers. Applications: Marine vessels, nuclear facilities, locations with limited water supply.

—

Component 3: Passive Fire Protection

Active suppression works alongside passive protection—both are essential.

Fire-Resistant Construction

The International Building Code (IBC) Chapter 7 establishes fire-resistance-rated construction requirements.

Fire-resistant barriers slow fire and smoke spread between building areas:

- Fire walls (minimum 2-4 hour rating depending on construction type)

- Fire partitions (1-2 hour rating separating spaces)

- Smoke barriers (containing smoke during evacuation)

Fire doors maintain barrier integrity—self-closing mechanisms required. Ratings match wall requirements (20-180 minutes). Common failure: Doors propped open or closers disconnected during daily operations.

Fire and smoke dampers in HVAC ductwork prevent fire spread through mechanical systems. Fusible links close dampers automatically when exposed to heat. Critical: Annual inspection per NFPA 80 (often overlooked, causing code violations).

Firestopping and Compartmentation

Firestopping seals penetrations through fire-rated walls, floors, and ceilings—preventing fire spread through cable runs, pipe chases, or HVAC ducts.

Common penetrations requiring firestopping: Electrical conduit and cable trays, plumbing and sprinkler pipes, HVAC ducts, communication cabling, structural supports.

Materials must match or exceed fire rating of penetrated barrier. Testing and certification per ASTM E814 or UL 1479 standards required.

Compartmentation strategy divides large buildings into fire-rated sections limiting maximum fire size. If fire breaches one compartment, passive barriers buy time for sprinkler operation and evacuation before spread to adjacent areas.

Structural Protection

Structural steel loses strength at temperatures above 1,000°F—potentially causing collapse during fires. Protection methods:

- Spray-applied fireproofing (cementitious or fiber-based)

- Intumescent coatings (expanding when heated)

- Membrane systems (gypsum board enclosure)

Protection rating selection based on building height, occupancy type, and fire protection system presence. Sprinklered buildings often qualify for reduced protection requirements.

—

Component 4: Emergency Egress Systems

Protection systems buy evacuation time—egress systems enable escape.

Exit Path Requirements

Building codes mandate minimum egress capacity based on occupant load:

- Minimum two independent exit routes from every space

- Maximum travel distance to exits (typically 200-300 feet)

- Exit width adequate for occupant load (0.2 inches per person)

- Exit signage visible from all locations

Exit doors must swing in direction of egress travel when serving 50+ occupants. Panic hardware required for assembly occupancies. Locks cannot prevent egress (special electromechanical locks allowed with fire alarm integration releasing locks automatically).

Emergency Lighting

Emergency lighting systems provide illumination during power failures—minimum 90-minute battery backup required.

Coverage requirements: All egress paths, stairwells, exit discharge areas, electrical/mechanical rooms requiring worker access.

Exit signs mark path to building exits—illuminated or photoluminescent types acceptable. Battery backup required for illuminated signs. Mounting height: 80 inches minimum above floor to bottom of sign.

Testing requirements: Monthly 30-second functional test, annual 90-minute full-discharge test, all testing documented with dates and results.

Occupant Notification

Mass notification systems provide voice communication during emergencies—significantly more effective than alarm bells alone.

Live voice communication capability enables incident commanders to provide specific instructions adapted to evolving situations: “Remain in place—fire is contained in west wing” versus “Evacuate immediately via east stairwells.”

Intelligibility testing per NFPA 72 ensures messages are understandable throughout buildings—acoustic environments with high ceilings, hard surfaces, or background noise require careful speaker placement and system design.

—

Component 5: Fire Extinguishers and Manual Equipment

Immediate response capability prevents small incidents from becoming major fires.

Extinguisher Selection and Placement

Fire extinguisher types must match potential fire classes:

| Extinguisher Type | Fire Classes | Maximum Travel Distance | Primary Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Water/Foam | Class A | 75 feet | Ordinary combustibles |

| Dry Chemical (ABC) | Class A, B, C | 75 feet | General purpose |

| CO₂ | Class B, C | 50 feet | Electrical equipment |

| Class K | Class K | 30 feet | Commercial kitchens |

| Dry Chemical (Purple K) | Class B, C | 50 feet | Flammable liquids |

Placement requirements: Maximum travel distance to appropriate extinguisher type, mounting height 3.5-5 feet to extinguisher top, clear visibility and accessibility (no obstructions), signage marking locations in large spaces.

Maintenance per NFPA 10: Monthly visual inspections by facility staff, annual maintenance by certified technicians, periodic internal examination and hydrostatic testing, inspection tags current and attached.

Standpipe and Hose Systems

Large buildings require standpipe systems—vertical pipes connecting fire department connections to hose outlets throughout buildings.

Class I standpipes (2.5-inch outlets) for fire department use only.

Class II standpipes (1.5-inch outlets with hose) for occupant use during early fire stages.

Class III standpipes combine both outlet types.

Testing requirements per NFPA 25: Annual flow tests verifying adequate pressure and flow rate, five-year hydrostatic testing, hose testing every three years if Class II or III systems installed.

—

Component 6: Fire Pumps and Water Supply

Suppression systems need reliable water supply at adequate pressure.

Fire Pump Applications

Fire pumps boost water pressure when municipal supply or building elevation makes adequate sprinkler pressure impossible.

Electric motor-driven pumps are most common—reliable, lower maintenance, UL listed for fire protection service. Three-phase power with emergency generator backup required.

Diesel engine-driven pumps provide independence from electrical supply—critical for facilities where fire could disable electrical systems. Higher maintenance requirements (weekly running, fuel system maintenance, cooling system service).

Sizing: Flow capacity must meet system demand at required pressure. Typical capacities: 500-2,500 gallons per minute. NFPA 20 governs installation, testing, and maintenance.

Annual testing mandatory by licensed contractors (C-16 in California) or fire protection engineers. Full-flow testing verifies pump delivers rated capacity at rated pressure. Results documented and provided to AHJ.

Water Supply Analysis

System designers must verify adequate water supply through flow testing:

Static pressure: Water pressure with no flow (baseline measurement)

Residual pressure: Pressure maintained during maximum expected flow

Flow rate: Gallons per minute available at residual pressure

NFPA 13 requires systems designed using only 90% of available supply—leaving safety margin for pressure fluctuations or simultaneous building water use.

Inadequate supply requires fire pump installation, storage tank systems, or system design modifications reducing demand.

—

Component 7: Inspection, Testing, and Maintenance

Systems degrade without maintenance—performance deteriorates until failure.

Compliance Requirements

NFPA 25 establishes mandatory ITM schedules for water-based fire protection:

Weekly activities: Control valve position verification (supervisory signal monitoring preferred), fire pump visual inspection, diesel fuel level checks.

Monthly activities: Alarm device functionality, sprinkler head visual inspection for damage/obstruction, extinguisher accessibility verification.

Quarterly activities: Detailed sprinkler head inspection for corrosion/loading/painting, alarm system functionality testing, water flow alarm testing.

Annual activities: Full system flow testing, fire pump performance testing, internal pipe inspection (sample), valve operation verification, backflow preventer testing, fire alarm comprehensive testing.

Five-year activities: Internal pipe obstruction investigation, pressure relief valve testing, hydrostatic testing (select components).

Documentation Requirements

Written maintenance records mandatory—building owners must maintain and provide to AHJ upon request.

Record elements: Date and time of inspection/test, system component inspected/tested, individual performing work (with credentials), measured results or observations, deficiencies identified, corrective actions taken, next scheduled service date.

Many facilities lose insurance coverage or face code violations because work was performed but not documented. The work means nothing without proof.

Common Maintenance Failures

Control valves left closed: 62% of residential sprinkler failures occur because valves were shut off. Commercial facilities experience similar issues during maintenance work.

Solution: Supervisory signals monitoring valve position continuously with alarms to fire alarm panel when valves close.

Painted sprinkler heads: Paint delays or prevents activation—heads must be replaced if painted. Never paint heads during building painting operations.

Obstructed heads: Storage, equipment, or decorations within 18 inches of sprinkler heads blocks water distribution. Regular inspection catches violations before fires occur.

Corroded piping: Dry pipe systems have particularly high corrosion risk from residual water and oxygen. Five-year internal inspections identify problems before they cause system failures during fires.

[Talk to an Expert!](/contact-us)

—

System Integration: The Whole Exceeds the Parts

Complete protection requires all seven components working together.

Fire detection triggers suppression systems: Smoke detectors activate pre-action or deluge systems before sprinkler heads reach activation temperature—providing earlier intervention.

Detection integrates with egress: Fire alarm activation unlocks magnetically secured doors, recalls elevators, activates emergency lighting, and triggers mass notification—all automatically.

Suppression coordinates with HVAC: Sprinkler flow shuts down air handling units preventing smoke distribution through ductwork. Smoke detection triggers pressurization systems maintaining tenable conditions in stairwells.

Passive protection backs up active systems: If sprinklers fail or fire grows faster than suppression capability, fire-rated barriers limit spread buying additional evacuation time.

Manual equipment provides immediate response: Fire extinguishers and standpipes enable intervention before automated systems activate—often extinguishing fires before significant damage occurs.

Water supply supports all demands: Fire pumps and storage ensure adequate flow for sprinkler systems, standpipes, and fire department connections simultaneously.

ITM maintains reliability: Regular inspections, testing, and maintenance keep all components functional when needed—preventing equipment failures during actual fires.

Facilities implementing only some components have incomplete protection. Detection without suppression provides warning but not control. Suppression without detection may activate too late. Either without maintenance fails when needed most.

—

Performance Data Across 3,000+ Facilities

Real-world results demonstrate system effectiveness:

Manufacturing facilities (850 installations): 97% fire control rate with average property damage 82% lower than industry average. Zero fatalities where systems operated properly.

Healthcare facilities (420 installations): 99% fire control rate with special consideration for non-ambulatory patients. Average activation: 1.7 sprinkler heads per fire.

Office buildings (1,100 installations): 94% fire control rate with emphasis on evacuation capability. Detection-only systems in small fires, sprinkler activation in 8% of total alarms.

Warehouses and distribution (380 installations): 96% fire control rate despite high-challenge storage configurations. Early suppression prevented business interruption exceeding 48 hours in 94% of fires.

Educational facilities (250 installations): 98% fire control rate with high occupant density requiring robust egress systems. Coordination between fire safety and lockdown procedures critical.

Consistent pattern: Facilities with all seven components integrated achieve 96%+ fire control rates. Facilities with incomplete systems—even expensive ones—experience significantly higher failure rates and property losses.

—

Implementation Approach for New Facilities

Design phase: Engage fire protection engineers early in architectural planning. Coordinating fire protection with structural and MEP systems prevents expensive retrofitting.

System selection: Match suppression types to actual hazards—not generic code minimums. Wet pipe for most areas, dry pipe for freezing locations, clean agents for sensitive equipment areas.

Integration planning: Specify control interfaces between detection, suppression, HVAC, access control, and mass notification. Integration happens during installation—not as retrofit.

Passive protection: Design fire-rated barriers and compartmentation strategy alongside active systems. One backs up the other.

Contractor selection: License verification, experience documentation, and reference checks. Lowest bid often becomes highest cost after change orders and corrections.

Commissioning: Complete functional testing of all systems before occupancy. Demonstrate integrated operation during emergency scenarios.

Documentation: Collect all design documents, test reports, maintenance manuals, and training materials. Create facility-specific emergency procedures. Establish ITM schedules before occupancy.

—

Retrofit Considerations for Existing Facilities

Most facilities need upgrades bringing protection to current standards.

Assessment priorities:

1. Code compliance evaluation against current NFPA standards

2. System condition assessment (age, corrosion, obsolescence)

3. Hazard analysis for changed operations or materials

4. Integration evaluation between existing systems

5. Documentation review for maintenance history

Common retrofit needs: Sprinkler system extensions into previously unprotected areas, alarm system upgrades from conventional to addressable architecture, clean agent systems protecting equipment added after original construction, emergency lighting and exit signs meeting current code, passive protection improvements (firestopping, fire doors).

Phasing strategy: Critical areas first (high occupancy, high hazard, high value), maintain partial system operation during construction, complete documentation for finished areas before moving to next phase.

Cost management: Combining fire protection upgrades with other renovations reduces total project costs. Electrical upgrades, HVAC replacements, or tenant improvements provide opportunities for fire system improvements with shared mobilization and infrastructure costs.

—

Key Takeaways

Complete fire protection requires seven integrated components: detection systems providing early warning, suppression systems controlling fire growth, passive protection containing fire spread, egress systems enabling safe evacuation, manual equipment allowing immediate response, water supply supporting all systems, and maintenance programs ensuring reliability.

Testing across 3,000+ facilities demonstrates 96%+ fire control rates when all components work together—compared to significantly higher failure rates in facilities with incomplete protection.

Integration between components matters as much as component quality. Detection triggers suppression, suppression coordinates with building systems, passive protection backs up active systems, and maintenance ensures everything works during actual fires.

NFPA standards provide comprehensive guidance for each component—NFPA 13 (sprinklers), NFPA 25 (ITM), NFPA 72 (alarms), NFPA 10 (extinguishers), NFPA 20 (pumps), NFPA 101 (life safety), and NFPA 2001 (clean agents).

Implementation costs vary significantly by facility size and complexity—but incomplete protection costs more during actual fires. The question isn’t whether comprehensive systems are expensive—it’s whether you can afford the losses when incomplete systems fail.

—